DECEMBER 2019 UPDATE: The Wyoming Outdoor Council and our partners have requested that the Wyoming Department of Environmental Quality inspect potential existing violations of Wyoming water quality standards at Moneta Divide, and we are still awaiting a reply. We are concerned that the DEQ involved Aethon, the project proponent, in its study of stream health that was in response to public concerns about potential impacts to wildlife and public health. The DEQ intends to reissue a revised permit for wastewater discharge in January. We’re also awaiting the Bureau of Land Management’s Environmental Impact Statement for the Moneta Divide project, which must evaluate wastewater disposal issues. Please stay tuned for how you can weigh in to protect our water, and tell the DEQ “Don’t Poison Boysen!”

This past spring, snowmelt unleashed just as heavy rains fell for several weeks, swelling the reservoir at Boysen State Park to capacity. The Bureau of Reclamation increased flows to 7,000 cubic feet per second below the dam, pushing water high along the banks of the Wind and Bighorn rivers, creating a challenge for drifters.

But the fishing was still hot.

“Yesterday we had two boats out, and each of our boats hooked up to about 40 fish — all in that 18- to 20-inch range,” fishing guide John Schwalbe said back in June.

Schwalbe, owner of Wyoming Adventures in Thermopolis, has guided on the Bighorn for 25 years, owing his livelihood to the Blue Ribbon trout fishery that produces big rainbows, browns, and cutthroat.

“I wouldn’t live in Thermopolis, Wyoming, if it were not for the Bighorn River that runs through it. It’s my livelihood, it’s the reason why I stuck around this area.”

— John Schwalbe, River Guide

A lot of his regular clients are locals who work in the oil and gas industry, and in addition to navigating the high water and figuring out what flies trout were hitting, the big topic of discussion this spring was the future of this fishery.

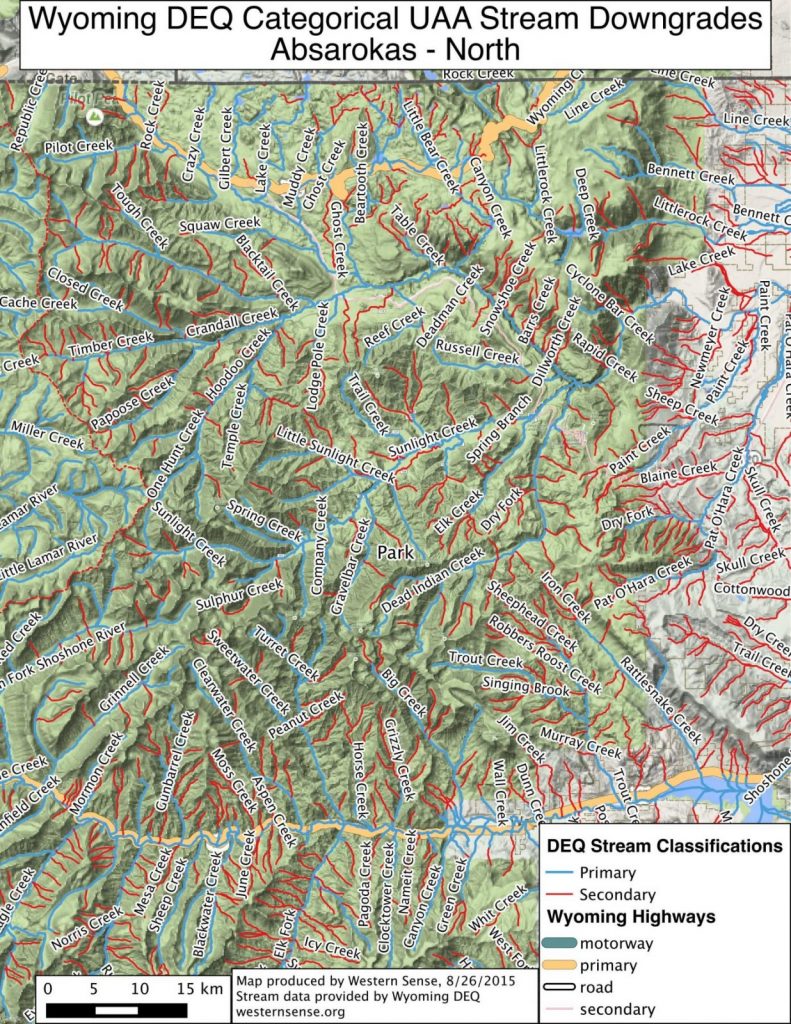

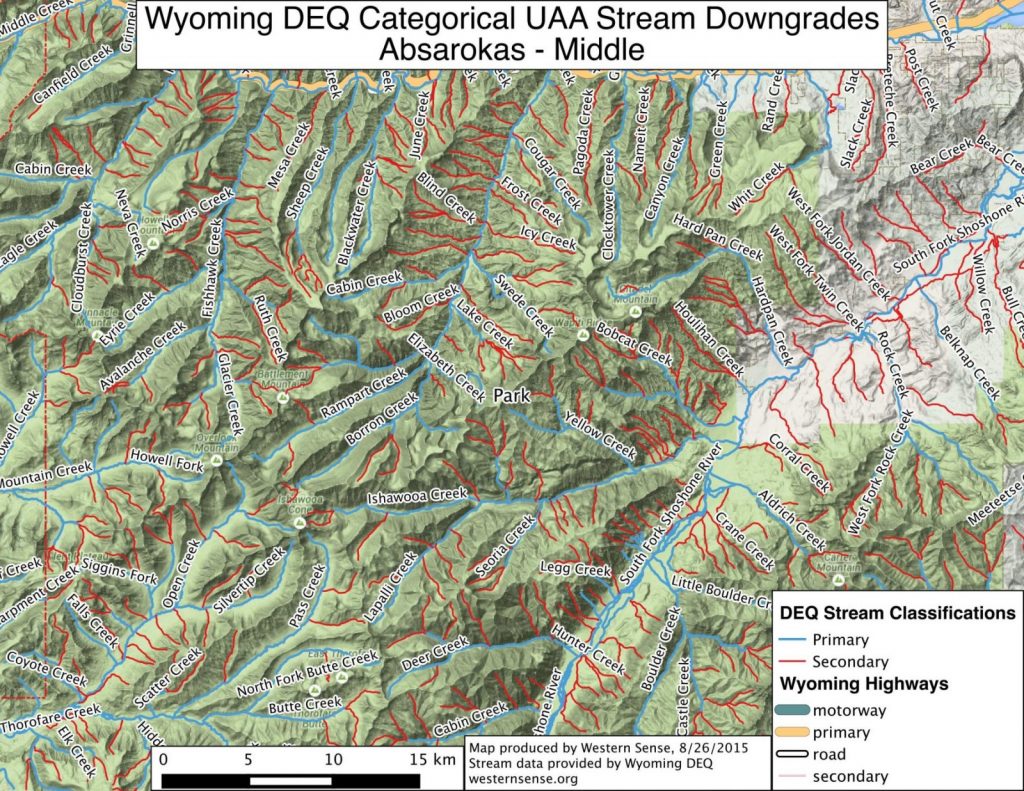

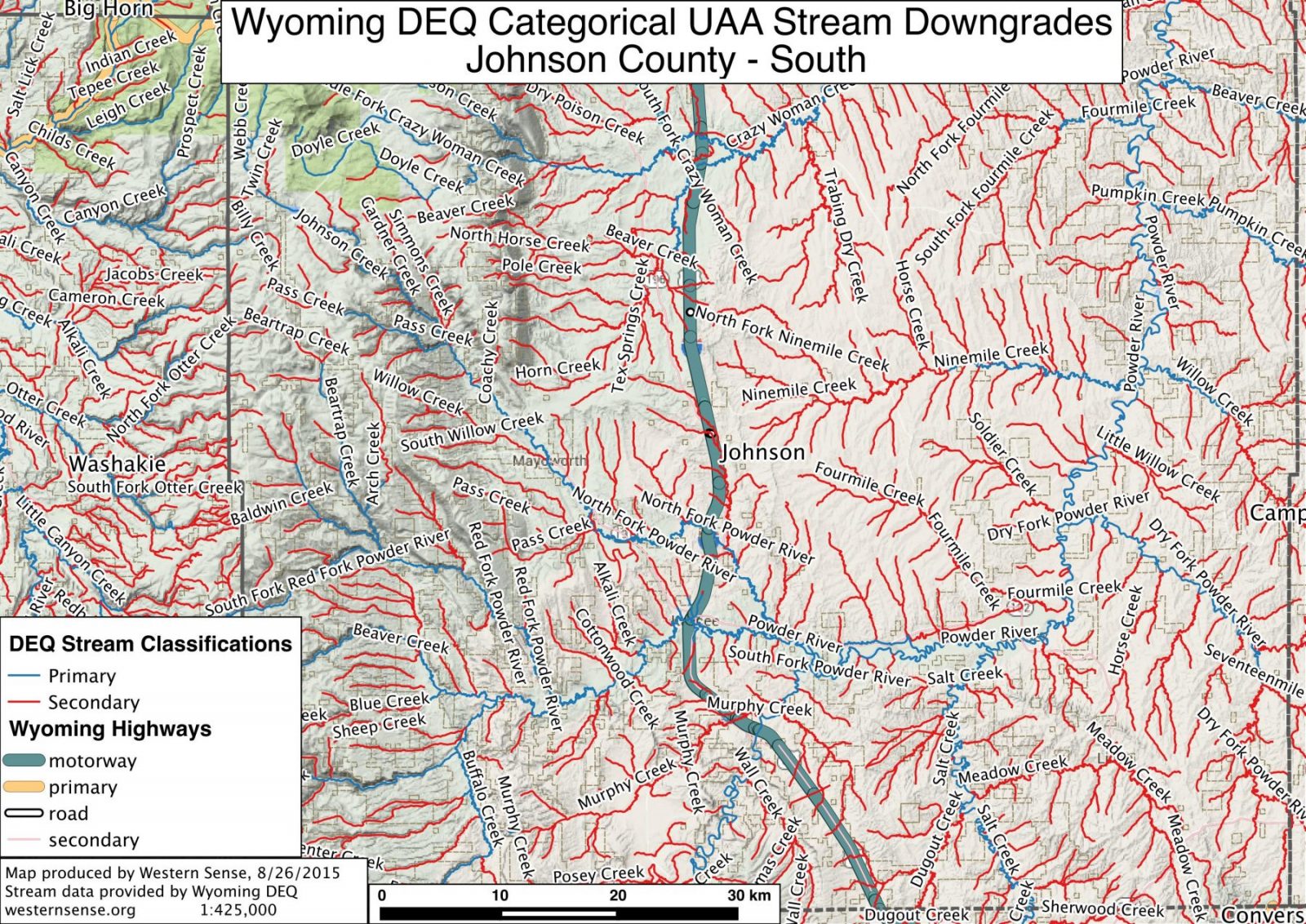

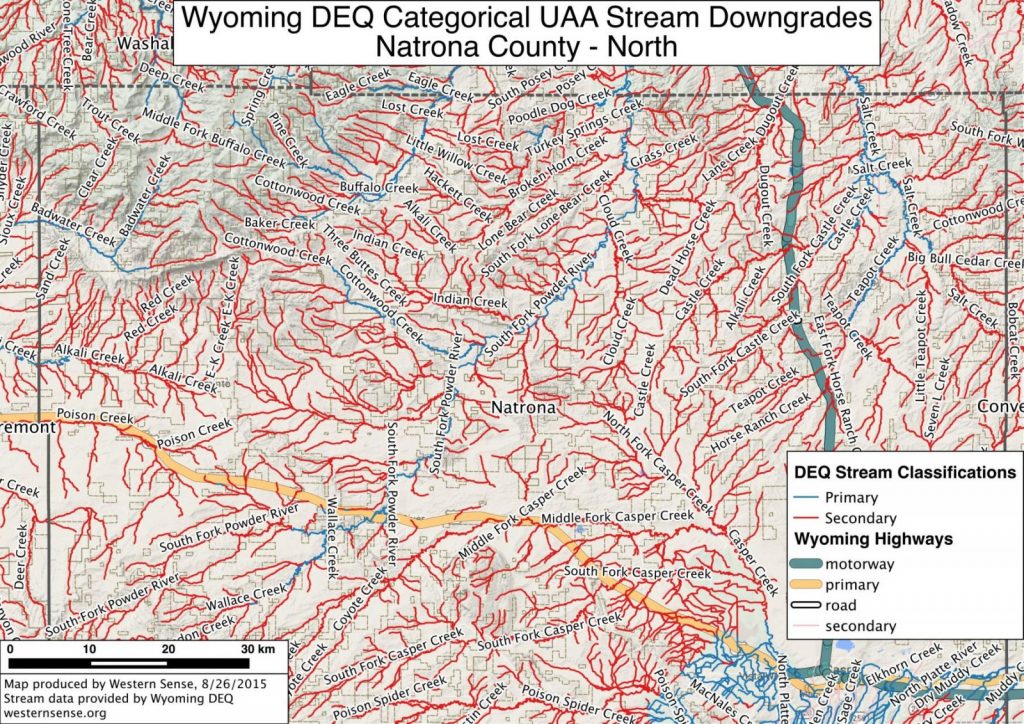

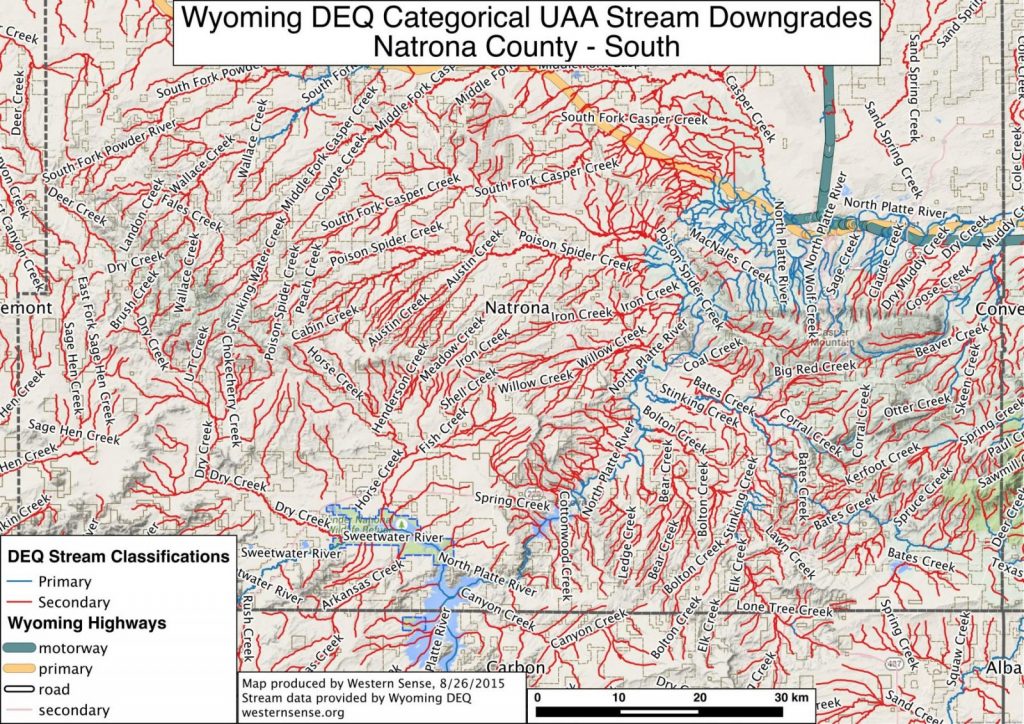

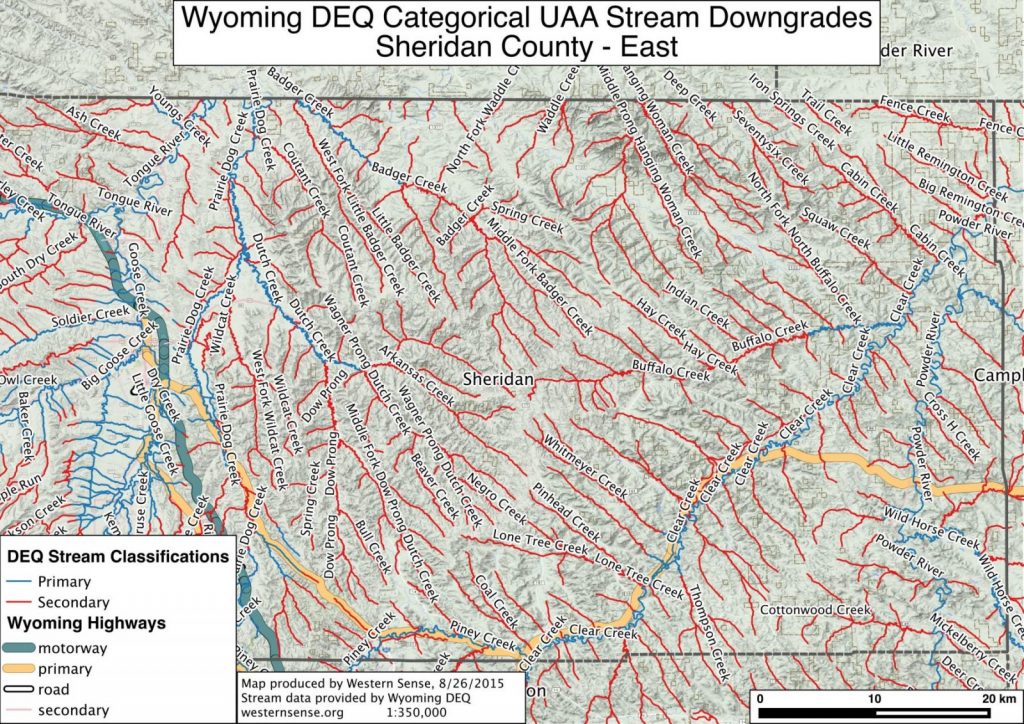

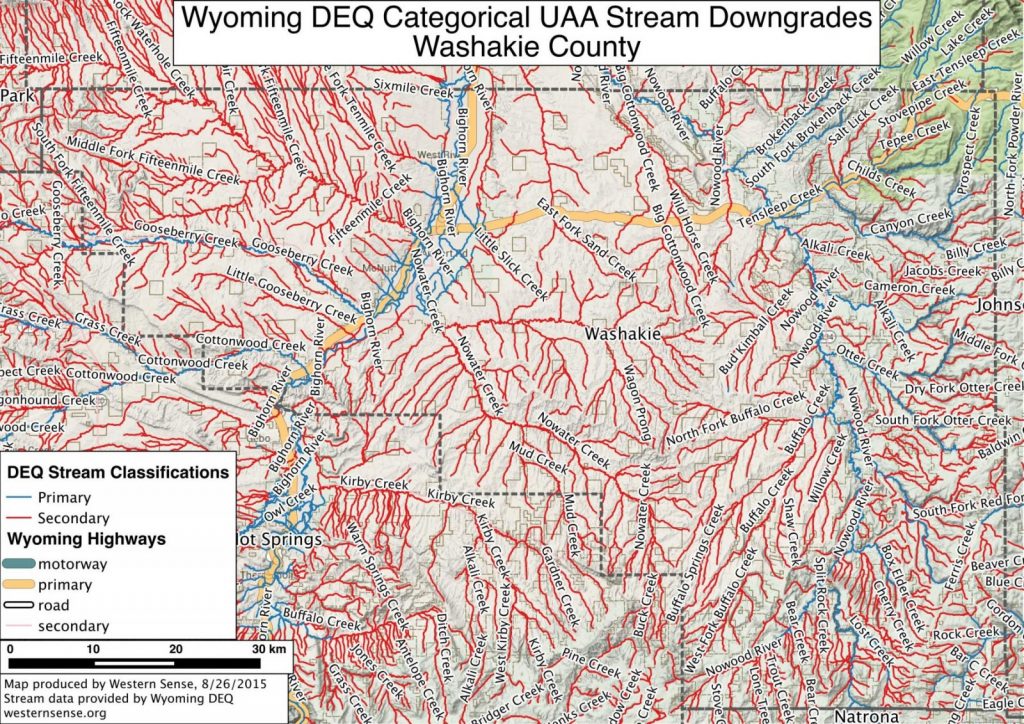

Upstream in the watershed is the Moneta Divide oil and gas field, where Texas-based Aethon Energy proposes to drill 4,100 new wells over the next 15 years — an economic boost for many communities in a part of the state that desperately needs jobs and revenue. But the company’s plan includes dumping up to 8.27 million gallons per day of “produced” oilfield wastewater — groundwater mixed in the oil- and gas-bearing formations — into tributaries of Boysen Reservoir.

The Wyoming Department of Environmental Quality relied on modeling from a consultant hired by Aethon to determine that decreases in water quality in the Class 1 Wind River were insignificant. The DEQ’s analysis also found that impacts to Alkali and Badwater creeks would meet regulatory requirements. As it turned out, neither conclusion was correct.

Although some residents want to see the drilling project move forward for the jobs and revenue, many worry that Aethon and the state didn’t do a thorough job of analyzing the plan and didn’t provide safeguards to ensure the viability of livelihoods that are tied to Boysen and to the Wind and Bighorn rivers.

“There’s a responsibility that we have here to manage our state well, but also put people to work. I’m all for that,” Schwalbe said. “But not at the cost of our watersheds and natural resources. Not at all.”

Clean water is too important to risk

With the help of partners and members, the Wyoming Outdoor Council hired hydrologists, aquatic biologists, and other scientists to conduct a detailed, expert analysis of the proposal by Aethon and the DEQ. The results were troubling. The analysis revealed significant flaws in the plan that would severely threaten aquatic life and municipal drinking water sources, as well as the economic and cultural values that tie Schwalbe and so many others to these iconic Wyoming waters.

“This proposal violates the Clean Water Act, the Wyoming Environmental Quality Act, and the DEQ’s own rules about implementing these important laws,” attorney and Outdoor Council Senior Conservation Advocate Dan Heilig said. “Fundamentally, though, the proposal unnecessarily risks the health and livelihoods of Wyomingites. It doesn’t have to be this way. There are other solutions.”

The Outdoor Council is not the only voice pointing out that good jobs and economic development should not be at odds with clean water and healthy fisheries. In many cases, they’re one and the same. Dusty Lewis is among a growing number of locals in Hot Springs County who hope to boost tourism in the area. Lewis owns Rent Adventure in Thermopolis, renting out drift boats, rafts, kayaks, and paddle boards.

“We spend a lot of time in the water, and we do a lot of fishing,” he said.

While Aethon and the DEQ assured the public that there’s no risk associated with the plan to use Boysen Reservoir as an oilfield wastewater mixing zone, Lewis and others were not fully convinced. There’s too much at stake, said Lewis.

“If the fishery were damaged, that would probably be the worst thing.”

He noted that everyone in Thermopolis recognizes the outsized role the Bighorn plays in the community, and suggested that economics is only part of the equation. The river and the outdoor way of life it supports is a huge part of the community’s identity. That’s why this proposal is so troubling.

“I’ve got a five- and seven-year-old — Fischer and Fletcher — and they are outdoor junkies,” Lewis said. “They would be some little angry rugrats if something happened. They would be like, ‘Dad, why didn’t you act more responsibly and help the river get saved?’ So I think about it for them. The next generation coming up has a lot to overcome.”

Lewis also serves on the town council in Thermopolis. The town draws from the Bighorn for its municipal water. A change in water quality could add to operational costs at the town’s water treatment plant. Alternate sources for municipal water come with their own costs. Locals worry that tapping aquifers nearby could affect the town’s world-famous hot springs, and tapping aquifers elsewhere would come at a significant expense.

“There’s a lot of variables when you talk about changing water sources,” said Lewis.

Sustaining clean water is a win-win

Based on the scientific and legal analysis, the Outdoor Council submitted comments to the DEQ in July asking that the agency go back to the drawing board. “A careful look revealed so many significant flaws in this plan that we’re confident it won’t stand without a fundamental revision to ensure that water quality standards are met, and that downstream users and livelihoods are protected,” Heilig said.

This story went to press before we could learn of the DEQ’s response to the Outdoor Council’s comments or its proposed next steps. We were encouraged, however, by the number of public comments urging the DEQ to deny the permit — including a powerful letter from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency that identified numerous significant flaws in the draft permit.

If the DEQ forwards its plan for Aethon Energy’s wastewater surface discharge permit without meaningful revision, the state may still face challenges to hold it accountable for safeguarding clean water resources. The Outdoor Council is committed to insisting that Wyoming’s clean water is protected.

As oil and gas leasing picks up around Wyoming, and as the Moneta Divide project expands, making sure that energy development doesn’t come at the expense of Wyoming’s clean air and water and healthy wildlife populations will continue to be a challenge.

It’s one worth meeting head on.

“Wyoming residents were given a false choice — that we must accept lower water quality and unknown risks in return for economic development,” Heilig said. “We know better. We hope that the DEQ takes into account the thousands of residents who rely on these iconic waters today and for generations to come.”