Where we site large-scale solar matters — and with the final draft of the Bureau of Land Management’s Western Solar Plan, we now have a useful template for proactively deciding where solar projects should (and should not!) be built on federal lands.

Back in April, we asked our supporters to engage in the public comment process for the updated Western Solar Plan, a once-in-a-generation opportunity to get solar siting right. If you submitted a comment on the draft plan, we can’t thank you enough! Because of your engagement, the final plan offers greater protections for Wyoming’s wildlife.

From draft to final, the BLM made a number of changes to the plan. Some are good, and some we’re not huge fans of. But on the whole, we’re pleased with how things shook out. Since the plan is rather hefty, we’ve compiled this guide to help you understand what it contains. (We’ll start with main takeaways, then, if you want them, we’ll dive into the nitty-gritty details.)

At the highest level, here’s what we know about the final plan:

- The plan includes BLM lands in Wyoming. (The previous Western Solar Plan did not include Wyoming.)

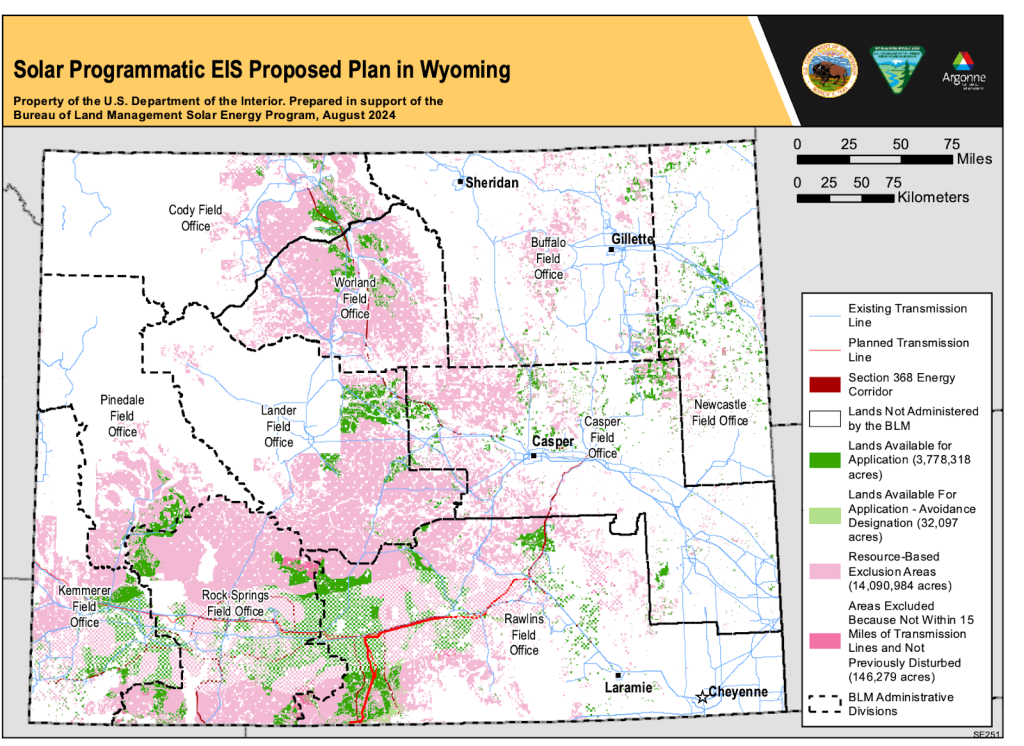

- 3.8 million acres of land in Wyoming are available for lease, or roughly 27 percent of BLM lands in the state. However, the BLM anticipates only 27,000 acres of actual development in Wyoming by 2045 to meet market demand for solar energy — roughly one percent of the total potential area available for leasing.

- The plan limits solar development using 21 resource-based exclusion criteria including Areas of Critical Environmental Concern, threatened and endangered species habitat, and Tribal Interest Areas, among others.

- The final plan adds significant protections for big game species. It excludes solar development from crucial winter range, parturition areas, and portions of migration corridors including high-use, stopover, and bottleneck habitat. The plan also helps clarify how new information and research could be used to update maps of big game habitat where development is not allowed. (We still have questions about how this process will work between BLM and state wildlife agencies and how frequently local land use plans will be updated.)

- The final plan adds features to improve environmental justice considerations and community benefit agreements that WOC and others advocated for. However, we think the BLM did not adequately take into consideration Tribal perspectives and should do more to collaborate with Tribes on when and where solar is authorized, as well as how to address conflicts in priority areas for Tribal communities.

- Areas available for solar leasing are limited to lands within 15 miles of existing or planned transmission and/or locations with previously disturbed lands.

- The final plan excludes development on Lands with Wilderness Characteristics that have been protected in local land use plans.

The final Western Solar Plan: A deeper dive

To understand why we needed an updated Western Solar Plan, we have to begin with some context. An update has been long overdue for three key reasons: First, the cost of solar energy has plummeted nearly 90 percent over the last decade. In many places, solar is the cheapest way to add energy capacity to the grid. Second, the technology surrounding solar energy has improved significantly, making solar energy more efficient and viable in northern latitudes and over a wide range of conditions. In fact, the efficiency of solar panels has increased roughly 40 percent in the last decade. Finally, federal policy is currently promoting incentives around renewable energy and decarbonization to address concerns over greenhouse gas emissions and climate change.

Taken together, these trends have led to rapid growth in the solar industry. For perspective, solar and battery storage made up over 80 percent of new U.S. electric generation capacity in 2024 — surpassing even the most optimistic projections around solar development.

These changes point to accelerating demand for locations to site large-scale solar projects, which in turn means that we need to proactively assess where future solar development on public lands is and is not appropriate. This is why BLM’s updated plan is so important: Failing to put protective side-rails in place now to direct future development could mean losing many of the conservation, wildlife, recreation, and cultural values that are so important to Wyoming.

(If you’d like to read more about why the Western Solar Plan is our chance to meet an important moment, see our blog about the draft plan from earlier this year.)

Now that we have the context in place, what follows is WOC’s analysis of the final plan’s important parts.

BLM lands in Wyoming were included in the plan.

This was not a sure bet initially and, in fact, a number of prominent leaders in Wyoming opposed Wyoming’s inclusion. We think that including Wyoming in the new update is a good thing, as it takes some of our best habitat and intact landscapes off the table before projects are being considered.

The final plan combines aspects of various alternatives within the draft.

The final plan limits solar development to:

- Areas outside of 21 key resource-based exclusion criteria. This includes exclusions for resources like Areas of Critical Environmental Concern, certain Lands with Wilderness Characteristics, Big Game Habitats, and Critical Habitat Areas for Threatened and Endangered Species. See the full table of exclusions here.

- Areas with a slope of less than 10 percent.

- Areas within 15 miles of existing or planned 69kW transmission or greater, and/or areas identified as previously disturbed lands, which generally have diminished resource integrity based on the U.S. Geological Survey Landscape Intactness model.

By increasing the allowable distance from transmission corridors in the final plan, the overall acreage available for leasing on BLM lands in Wyoming increased substantially. The practical effect of this change would give industry more acreage to consider development on.

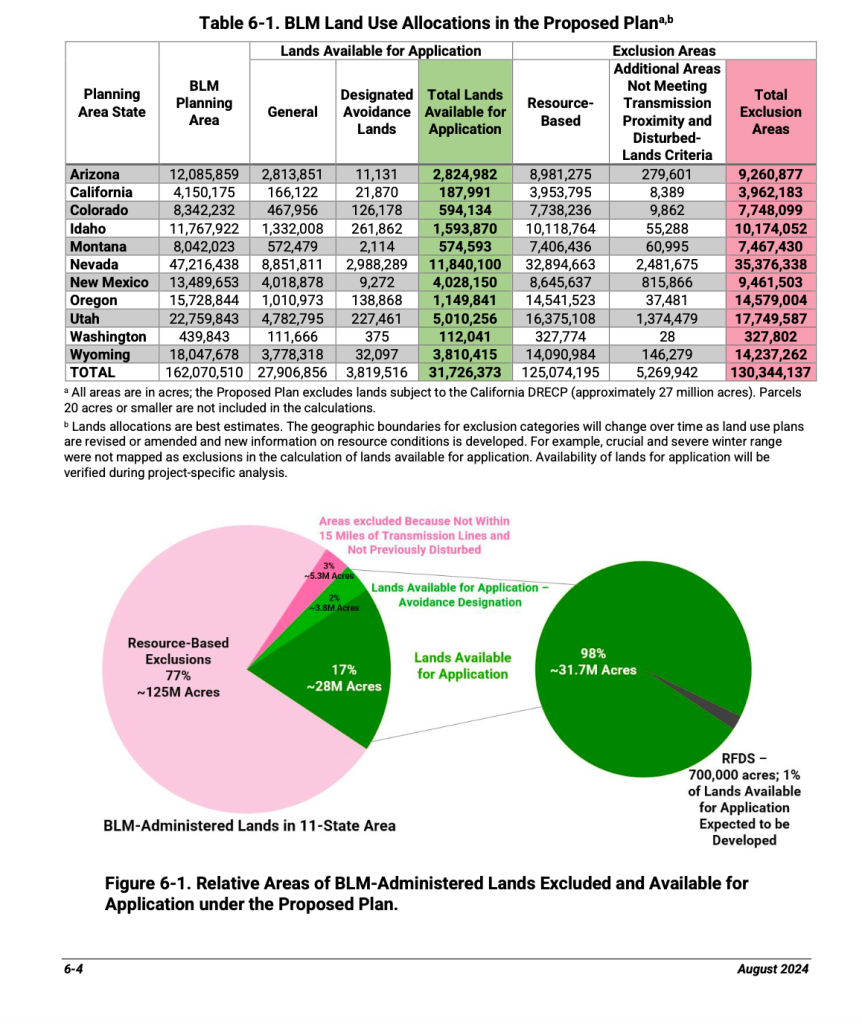

It’s important to note that the reasonably foreseeable development scenario has not changed — the best guess is demand for solar projects on public land in Wyoming will not exceed 27,000 acres by 2045. It’s also worth noting as a comparison number that there are more than 8 million acres of BLM land in Wyoming with existing oil and gas leasing. Table 6-1 below provides a state-by-state accounting of total lands available for application and exclusion areas.

The plan better protects big game species.

The resource exclusion criterion for big game was significantly improved to protect critical habitats and migration corridors. In the initial draft, solar development would have been allowed in migration corridors, crucial winter range, and parturition areas unless local BLM offices had their own protections in place (which is not the case for most Field Offices in Wyoming). Now, future solar development on BLM lands will be excluded in portions of big game migration corridors mapped as “high use,” migration pinch points, bottlenecks, and stopover areas, not to mention parturition areas and crucial winter range habitat. Additionally, BLM created a new “avoidance designation” for lands intersecting migration corridors mapped as “medium and low use.” This new designation would require developers to work with state wildlife agencies like the Wyoming Game and Fish Department to avoid harm to wildlife in order to proceed with proposed projects in avoidance areas.

This is a huge win and something that WOC and our allies fought hard to ensure. From the beginning, one of the most significant concerns with utility-scale solar development is its impact on wide-ranging wildlife that need open space to move freely across the landscape. The strengthening of this exclusion criterion gives us confidence that future projects will avoid situations like the one that unfolded at Sweetwater Solar, where thousands of pronghorn were pushed into a narrow road corridor because the project was built in a pathway used by the animals to access critical winter range habitat.

The plan clarifies how new information could be used.

BLM clarified the process by which new information, research, and habitat maps could be updated into the final plan as we learn more and refine our knowledge of the important movement patterns and habitat needs of wildlife. This provides a compelling incentive and opportunity to map additional migration corridors and update habitat maps for big game in the state.

Notably, a lack of mapped and published migration corridors in Wyoming reduced the amount of land designated as either “exclusion” or “avoidance” areas. Compared to some other states (like Nevada), Wyoming has a relatively small number of exclusion and avoidance areas for big game migration corridors, despite having some of the best habitat and copious data to draw on to model additional migration corridors. From our perspective, this provides another compelling reason why Wyoming must continue mapping and recognizing migration corridors, not to mention updating big game crucial winter range maps, so that this critical information can be used to better protect our state’s wildlife resources in future federal land management processes. Figure 6-3 below shows areas where solar leasing would currently be excluded and avoided based upon migration corridor data.

The plan excludes Lands with Wilderness Characteristics.

For Lands with Wilderness Characteristics, we are extremely pleased to see the BLM acknowledge the value of lands that still hold their wildness by excluding designated LWCs outright and considering all others — including those nominated by citizens — during project-level decisions. These areas are an important piece of the interconnected whole. They safeguard the ecological integrity of the greater landscape and provide meaningful opportunities for Tribal members and local communities to connect with and sustainably steward the land.

Other considerations

During the public comment period on the draft plan, WOC and the Wyoming Wilderness Association raised a number of other important issues. These were addressed (to various degrees) as programmatic design features in the plan. These included:

- A requirement to identify whether the lands within and immediately adjacent to the proposed solar energy project have been assessed for wilderness characteristics or have been included in a citizen’s wilderness inventory or proposal.

- Requirements around Tribal consultation considerations and the avoidance of impacts to resources and landscapes important to Tribal communities.

- Requirements around environmental justice considerations and guidelines encouraging the use of community benefit agreements by developers.

We are still working to understand the exact implications and nuances of these requirements, especially as they relate to Tribal consultation and what mitigation looks like when impacts to Tribal resources occur. The mitigation concepts proposed in the final plan fail to recognize the place-based importance of these resources for Tribal communities. As such, mitigating impacts by guaranteeing access to a resource in a different location, or by transplanting species, misses the point of those areas themselves being important — not just the area’s plants, minerals, or animals.

Conclusion: Looking forward

All in all, BLM’s final plan shook out positively for big game species and a number of the other resources and values that are critical from a conservation perspective. Given the relatively small amount of development forecasted in Wyoming, WOC would have preferred the final alternative to be more prescriptive in limiting development to only the least impactful locations.

As we think about the future of renewable energy development, it is only going to become more important to focus on project-specific NEPA analyses to understand the local and overall cumulative effects of proposed development. Decisions made at the project level, even down to the type of fencing and ways that solar panels are mounted, can have a huge impact on the environment and wildlife. Similarly, as with other forms of development, careful attention needs to be given to lifecycle considerations such as impacts from raw material extraction, component recycling, and reclamation for utility scale solar projects. Our commitment to Wyoming and our supporters is to scrutinize these projects as they’re proposed and take action when changes or improvements are necessary.

The renewable energy boom is coming, and one of the biggest challenges we face is the need to simultaneously reduce our carbon emissions to address a changing climate, while also protecting the best of the habitat and natural resources we have left. Locally, these goals can find themselves at odds, despite the fact that globally, they are largely the same.

In this transition, it’s important to recognize that Wyoming sits in a place of abundance — for its renewable energy potential and its outstanding habitat, recreation, and cultural resources. With so much to lose, we must proceed carefully and thoughtfully. The Western Solar Plan is a step in the right direction, but much more work still needs to be done to ensure that all large scale energy development is done responsibly with both environment and people in mind.

Header image: Bureau of Land Management | Flickr CC