In Wyoming’s Red Desert, the necessity of truly big-picture, holistic thinking around conservation advocacy is on full display. For one, it’s home to big game herds that require intact habitat throughout the length of migration corridors that span hundreds of miles. For another, it’s a place that has been stewarded by people for millennia, whose descendents are still here — and whose voices are critical for any conversations about how this land should be managed.

While obstacles to this kind of big-picture thinking are many, the sheer scale of the landscape presents a unique challenge: At more than a half-million acres, how do you wrap your mind around an area the size of the Red Desert?

Recently, Tribal Engagement Coordinator Big Wind Carpenter worked with EcoFlight, a Colorado-based organization, to share a bigger-picture perspective of the desert … from high above, in a small 6-seater propeller plane!

During the flights, Big Wind narrated a loop over the Red Desert for Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho elders, pointing out many of the cultural resources that hold special significance for more than a dozen Tribes with connections to the land. We sat down with Big Wind to hear about their work with EcoFlight and to learn what insights might be gained from taking to the skies.

[Interview edited for length and clarity.]

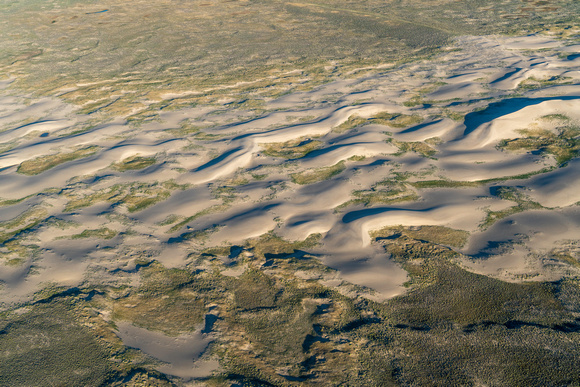

Images: EcoFlight

You’ve been sharing the values of the Red Desert with others for years now, but primarily with vehicle tours. How does EcoFlight fit into the work you’ve been doing there?

You could spend your entire life exploring the Red Desert — it’s that big of a landscape. When we leave Lander on a vehicle tour, whether we’re taking elected officials, Tribal people, WOC members, or donors, we know that it’s going to be an all-day trip, because a lot of these areas have long distances between them.

For people who don’t have that time or that mobility, I think it’s important that we try to work out a different tour for them. The intention for this year’s flight was to get some Tribal elders out there. We were able to get Reba Teran, an Eastern Shoshone elder and language teacher, and Mary Headley, a Northern Arapaho elder who teaches at the Arapaho Immersion School, to join us. And then they also brought their helpers with them because they have mobility issues. We’re trying to make sure that people who have mobility issues are still able to see these places, and have these discussions.

Tell us a little about your flight path — which parts of the Red Desert did you get to see?

We did two flights that morning, and we kind of did a loop of everything north of I-80. We left the Lander airport early that morning, flew over Red Canyon, flew to where the Great Divide Basin starts over by the Oregon Buttes and the Honeycomb Buttes. Then we moved down to the Killpecker Sand Dunes and Boar’s Tusk. From there, we flew over the White Mountain petroglyphs, checked out Steamboat Mountain, and came back up through the Wind River Range.

For someone like you, who has spent so much time out in the Red Desert, what’s it like to see it from the air?

I think the Red Desert is such a special place, because it has all of these different microhabitats within the area that it covers. You have the south side of the Winds, and the sand dunes, and areas of sagebrush. The plains, the desert, and the mountains meet in this area, but you don’t understand completely until you’re thousands of feet above it. I think the EcoFlight is a very powerful tool to be able to visualize how interconnected these habitats are to one another. It’s such a beautiful thing.

Could you share some of the highlights of the flight?

Being able to see the sand dunes moving in real time was a highlight. The Killpecker Sand Dunes are the largest living sand dune field in North America. When you’re on the ground, there’s always a steady wind, and you can kind of see the sand moving. But when you have a bird’s eye, you can actually see where they’re traveling across the landscape.

Also, there were also some pretty good migrations of antelope coming down off the mountains. Especially knowing how diminished those populations are after last winter, it was amazing to see just how resilient these animals are to be migrating across the land.

What was it like to share an aerial view of the Red Desert with the elders who joined you? And with other, younger Tribal members?

For both Reba and Mary, especially as culture and language teachers, I think it was important for them to be able to tell us the names of these places, and what those names meant, and why they were named a certain way. As an Arapaho person myself, being in a situation where Mary was educating other Arapahos who didn’t know those areas was really impactful. I have Shoshone family (although I’m not a Shoshone Tribal member), so being out there with Reba and hearing their stories, hearing their names, and why they’re named those things felt very impactful to me, too.

Over a dozen Tribes have relations with that landscape: The Shoshone, the Crow, the Cheyenne, and many others have stories about that land and their connection to that landscape. Some of those Tribes, their stories go back thousands of years. So I think it’s really important that not only are those stories told, but that those stories are shared with the next generation. Not only did we have the elders, but we had young people on both of those flights who were able to hear from the elders, and I think that made this very significant.

I think that’s interesting, because you’re in a role where you’re the tour guide. But you’re also learning from your elders, too.

Yeah. I think that’s a part of our culture, as Indigenous people. We look to our elders for guidance, we look to our elders to be able to tell stories. There’s places like the Birthing Rock, and the White Mountain petroglyphs, and all these other sacred sites that are found in the Red Desert. If we don’t relay this information, it will be lost. So it’s important to ensure that our elders are able to have the space to pass on these stories to young people.