In Wyoming and across the U.S., tribes and tribal lands bear scars from the country’s nuclear programs. From abandoned radioactive waste to land seizures to the cancer-causing debris of weapons testing, tribal communities have been disproportionately impacted by nuclear development and its lasting consequences. Unfortunately, in the critical discussions surrounding nuclear projects, the voices of nearby tribal communities have often been sidelined or altogether ignored.

The Susquehanna-Western uranium mill, near Wyoming’s Gas Hills, was established during the mid-century uranium boom on tribal lands sold under duress. When it closed in 1963, nearly 1.8 million cubic yards of radioactive waste were left behind — and the Northern Arapaho and Eastern Shoshone Tribes are still dealing with the consequences.

Now, as the discussion around storing the nation’s high-level radioactive waste in Wyoming heats up, it’s more important than ever to learn from Susquehanna and other historical and ongoing injustices.

Below, Big Wind Carpenter and Jennifer Fienhold, WOC’s tribal conservation advocates, detail the fallout from the Susquehanna mill. They also share how, despite marginalization of tribal voices, advocates continue to demand justice for their communities and their land. As Jennifer puts it, “You will never read about the tribes being the unsung heroes of these tales, which is the biggest injustice of all.”

Big Wind Carpenter: A uranium mill’s toxic legacy

For many, the uranium boom of the 1950s was a sign of progress for the country, but for the people of Arapahoe, it resulted in a toxic legacy. When uranium mining began in the Gas Hills, a local milling site was required to process the uranium ore. The land chosen for the mill site was on the Wind River Reservation and belonged to members of my family. The Bureau of Indian Affairs came to our families to buy the land for the federally funded project. When they refused, BIA coerced some into signing documents, promising payments that never arrived. Those who resisted were threatened with arrest and forced off their own land. The mill site was then constructed and operational within a year’s time.

Although the project was brief, its impact lingers today. The Susquehanna plant operated for only five years before closing, but when it shut down, it left behind a 70-acre unlined impoundment of tailings — approximately 1.8 million cubic yards of low-level radioactive waste.

The Department of Energy removed the tailings in the late 1980s, claiming the danger was eliminated. This was a false promise. Over time, rain and snowmelt washed radioactive materials deep into the ground, polluting the water supply. This created an underground uranium plume — a silent threat that continues to grow, expanding from 20 to 27 acres in recent years and inching closer to the Big Wind River. This experience has left a deep scar on our community. We have seen loved ones suffer and even lose their lives from illnesses linked to radiation exposure from using tainted well water.

Excerpted from a January 20, 2025 post on the WOC blog. Read the full post here.

Jennifer Fienhold: The story’s unsung tribal heroes

You can find a full Department of Energy report detailing the remedial efforts around the Chemtrade mill (formerly the Susquehanna mill) online. However, what you will not find in this report is the fight brought to the federal government, the Department of Energy, and the Environmental Protection Agency by the tribes.

Both the Northern Arapaho and Eastern Shoshone Tribes monitored the impacts of this waste. After years of the surrounding community of Arapahoe being exposed, cancer levels began to rise. These consequences could also be seen in local wildlife, which began to show telling signs of radioactive exposure, but perhaps what was most alarming, a plume had formed under the plant and contaminated the local water sources. It would take an eight-year battle, diligence, and advocacy for basic human rights, but in 1988, the Tribes finally made headway. The Department of Environmental Quality alongside the EPA were forced to initiate remedial efforts to assist in addressing the long-standing contamination taking place as a result of negligent handling of nuclear waste.

In the end, it was decided to move the waste to Gas Hills, the original location of the uranium mining. The rationale behind this decision: take it back to where it came from. However, there had been other conversations. Within the same remedial report was also the proposal for other sites, 18 of them. Of these, three were seriously considered, and one was on the reservation.

Even two warring tribes, who could be found in tumultuous disagreements in the best of times, united to send the clear message that they did not want radioactive and nuclear waste stored on their lands, and made it clear they were not to continue to be tasked with environmental consequences that had already been forced upon them.

Excerpted from an unpublished account of Jennifer’s recent trip to Yucca Mountain, Nevada. Yucca Mountain was once the proposed repository for the nation’s nuclear waste, until the Western Shoshone, whose treaty land includes the site, successfully opposed the project. Stay tuned for the full account.

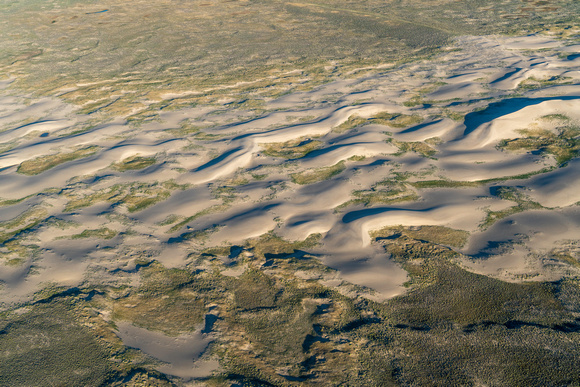

Image: A Susquehanna-Western uranium mill in Karnes County, Texas.