Will advanced nuclear technology usher in a clean energy utopia — or deepen existing problems?

LATE ON A WEDNESDAY AFTERNOON in a nondescript conference room in Casper, the people filling rows of plastic chairs lean forward in their seats. Reporters lining the back wall raise cameras and audio recorders, straining to catch every word. The air hums with tension as one after another, members of the public speak into a microphone and address the lawmakers seated before them.

The people have traveled here, to the July 2025 meeting of the Wyoming Joint Minerals, Business, and Economic Development Committee, to voice their opinions on a draft bill that would help clear the way for a first-of-its-kind nuclear manufacturing facility near Bar Nunn. The proposed facility would build “microreactors,” which are portable nuclear reactors — sort of like a shipping container-sized diesel generator, except with nuclear fuel — that would aim to provide reliable power for military installations, hospitals, and remote towns.

Murmurs of approval and frustration rise from the crowd as nearly 40 people share everything from heartfelt pleas for caution to hopeful portraits of economic prosperity. At times the tension boils over. “You’re shoving it through!” one commenter shouts, amplifying what several others have declared: that a speedy approval of the measure would disregard the concerns of community members. The chairman’s gavel cracks over the woman’s shouts. The proceedings continue.

Finally, long after afternoon has turned to evening, the last comment has been heard. What happens next is something of an anticlimax: The legislators agree to table the bill — effectively suspending it from consideration, while leaving the door open to discuss the topic at a future meeting.

But they never get the chance. In October, amid the regulatory uncertainty and public outcry, Radiant Nuclear, the company behind the project, pulled the plug on its plans in Wyoming, announcing that it would build its facility in Tennessee instead.

Some people breathed a sigh of relief. Others lamented what they saw as a missed opportunity. But for everyone, this is just the beginning of a much bigger conversation.

The proposed Bar Nunn facility may be off the table, but interest in advanced nuclear technologies is only growing, and industry has its eyes on Wyoming. In 2025 the Trump administration issued four executive orders to expedite licensing and build nuclear power generation capacity. And Wyoming’s favorable tax environment, plentiful open land, and skilled energy workforce make it attractive for nuclear development. Which is why, advocates say, it’s time for Wyoming to make a comprehensive plan governing nuclear energy.

The problem is, there are still a lot of unknowns when it comes to advanced nuclear energy. The technologies on the horizon are largely untested, and important questions remain about their safety and affordability. These unknowns could have serious consequences for Wyoming, for generations to come. And policymakers need to carefully consider the consequences as they weigh how much — and what kind of — nuclear development to allow in the state.

INTEREST IN NUCLEAR ENERGY IS SURGING in part because it’s seen as a way to meet rising energy demands, driven largely by the growth of AI and data centers, without contributing to climate change.

Traditional nuclear energy, with its high price tags, burdensome waste, and painful history of catastrophic meltdowns, has had a rocky past. But the advanced designs coming to the fore these days, proponents say, could power America’s future in an affordable and safe way, while also curbing fossil fuel emissions.

“Advanced nuclear technology” can mean a lot of things. But what’s garnering the most attention from both industry and the public are “small modular reactors,” or SMRs.

Proposed SMR designs vary wildly in their fuel, cooling systems, and power output. The most basic SMRs are scaled-down versions of traditional reactors, of which there are currently 94 in operation across the country, supplying 19 percent of America’s electricity. But their designers say SMRs have important advantages over traditional reactors: They will produce less waste, for one. And because components would be manufactured in a central facility before being assembled at a power plant site — sort of like Lego building blocks for nuclear energy — they could theoretically be deployed much faster. (Microreactors, like the ones Radiant hoped to build, are even smaller than SMRs; while microreactors are designed to be portable, SMRs are not.)

SMRs are also being touted as eminently affordable. Once SMR designs have made it over research and development humps, their size and modularity will lead to great cost efficiencies, Erik Funkhouser, executive director of the nuclear advocacy organization Good Energy Collective, says. That means they are more likely to be built: A large reactor costing $12 billion may be very difficult to fund, for example, but $1–2 billion is comparatively easy. SMRs would be more similar to the energy output and cost of a natural gas plant, Funkhouser says, “and we fund those day in and day out.”

Nuclear proponents hope such advanced designs will usher in a “nuclear renaissance” that will reshape the way we supply electricity to the grid while solving climate change. But other experts caution that nuclear’s economic problems aren’t going away and that commercial deployment of advanced technologies is still a distant dream. Moreover, they worry a “renaissance” could deepen problems around safety and disposal of radioactive waste.

DR. ALLISON MACFARLANE speaks with the measured, patient air of someone who has explained nuclear energy policy thousands of times. And she has: From 2012 to 2014, Macfarlane, a geologist by trade, headed the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, the federal agency that licenses the country’s nuclear energy projects.

Macfarlane sees many problems with a potential nuclear renaissance — starting with economics. The financial promises being made about SMRs simply aren’t realistic, she says. In her tenure as NRC chair, she oversaw licensing for three different SMR projects. Two of these projects failed in early stages because of concerns that they wouldn’t be economically viable. The third, developed by a company called NuScale, made it further along. But in 2023, this project also collapsed for economic reasons.

Traditional reactor projects have long suffered from construction costs that balloon far beyond initial projections, and SMRs are susceptible to these cost overruns, too. But they also have another issue to contend with: what experts call economies of scale. While an individual SMR might be cheaper to build than a large nuclear power plant, Macfarlane explains, you’d need several of them to generate the same amount of power. In the end, it would be cheaper to build one big plant than five small ones.

The bottom line for Macfarlane? Traditional nuclear power plants haven’t been cost-effective, and smaller reactors won’t be either. Other advocates fear that if they are built despite this, electric utility customers — homeowners, renters, and businesses — will be the ones to suffer as utilities look to recover their inevitable losses.

The problem is, there are still a lot of unknowns when it comes to advanced nuclear energy. The technologies on the horizon are largely untested, and important questions remain about their safety and

affordability.

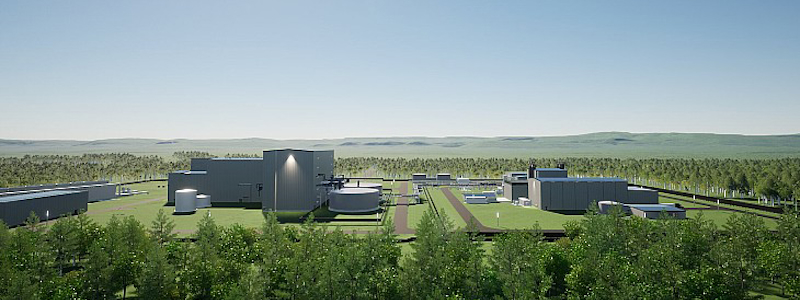

IN 2024, TERRAPOWER, A BILL GATES-FUNDED VENTURE, broke ground on its experimental nuclear power plant near Kemmerer — Wyoming’s first. The theoretical power output of TerraPower’s reactor is just above the threshold for what many consider to be an SMR. But its design, which uses molten sodium as a coolant instead of the water that traditional “light water reactors” use, is a perfect example of the advanced technology that proponents think will power a zero-emissions future.

The problem, Macfarlane says, is that these kinds of advanced nuclear facilities take a very long time to become operational. And we don’t have much time to curb the worst impacts of climate change.

“When you engineer anything — a fighter plane, or bridge, or nuclear reactor — you design it on your computer and then you have to build a scale model,” Macfarlane explains. As a design is scaled up and into three dimensions, aspects will shift and adjustments must be made, and then more adjustments must be made when moving from scale model to commercial scale. “With small modular reactors, we are at the computer model stage.”

There are only two SMRs being demonstrated in the Western world, according to Macfarlane: the Kairos reactor in Tennessee and the GE Hitachi BWRX in Ontario. Neither have completed construction. And the rest, she says, are so far from commercial deployment that they are basically figments of imagination.

Even TerraPower’s project in Kemmerer fits into this category, she says. While the project has cleared important hurdles, it has not yet received its construction permit from the NRC. And the gap between the design phase and large-scale commercial deployment for it and other advanced nuclear technologies could be on the order of three decades.

That’s why Macfarlane loses her patience when proponents laud advanced nuclear technologies as the silver bullet to combat climate change. “I’ll try not to be too colorful in my language…. If we had 20 years to fart around and perfect this technology, great,” she says. “But we don’t have endless time. We have to address this problem now.”

AT THE JULY MINERALS COMMITTEE MEETING IN CASPER, much of the opposition to Radiant’s facility had to do with waste. High-level radioactive waste, an unavoidable byproduct of nuclear power generation, produces fatal doses of radiation and could lead to far-reaching impacts on people and the environment if leaked into ground or surface water. Radiant’s plan involved storing waste from its microreactors onsite in Bar Nunn.

Wyoming law prohibits spent nuclear fuel from being stored within the state. But the company was asking for an exception. (A similar exception was given to TerraPower years earlier.)

In the short term, we actually have pretty foolproof ways to store nuclear waste, Macfarlane says. The current storage standard is within “dry casks,” or large steel canisters surrounded by thick concrete. And these work well: Even dry casks tipped over and inundated during the Fukushima disaster, for example, were undamaged.

But people are correct to worry about the long term. High-level waste remains radioactive for tens of thousands of years. While dry casks will hold waste safely for decades, perhaps even for a century, there’s no way to avoid their eventual degradation, Macfarlane explains. That means someone must always be monitoring them, and someone must foot the bill when it’s time to change them out. “The question of who’s going to pay for this 100 years from now is not answered at all,” Macfarlane says.

Another source of uncertainty is the lack of a federal site for permanent disposal of high-level waste. In TerraPower’s case, the company is allowed to temporarily store waste from their operations onsite, until a national repository is established. But such a site doesn’t yet exist. And the prospect of establishing one in the foreseeable future is bleak, meaning that waste would likely be stored within the state for far longer than “temporary” might suggest.

Wyomingites have good reason to be cautious about radioactive waste. From 1958 to 1963, the Susquehanna-Western uranium mill near Riverton processed uranium ore on land seized from Wind River Tribal members through eminent domain. When it shut down, a 70-acre pile of radioactive tailings was left behind.

Without a lining to keep it contained, waste soon seeped into the groundwater. Local families began experiencing cancer at alarming rates — an apparent impact of the radioactive plume that continues to this day.

When remediation efforts began, tribal members were often excluded from the decision-making process. “We were stymied at every turn,” says Gary Collins, a Northern Arapaho member involved in the discussions. He describes an atmosphere of broken promises and disregard for the people bearing the waste’s cancerous brunt.

Today, decades later, the waste has been removed. But the danger of contamination lingers, unseen by the people who live nearby. Collins rattles off a handful of local families impacted by cancer. “When you drive by here, you don’t see anything different,” he says. “You see a vast open field. You see somebody’s cows out there grazing away.” Collins pauses. “Are you eating those cows?”

Uranium processing is not the same as a nuclear power plant or nuclear manufacturing facility. But the story of the Susquehanna mill tailings offers a troubling lesson: When radioactive waste isn’t given the diligence it deserves, the impacts, which can last for generations, often fall on the most vulnerable communities.

How to store radioactive waste safely, in both the short and long term, is an important question. But what about other safety concerns? After all, nuclear energy still carries the stigma from catastrophic meltdowns at Chernobyl and Fukushima. Would advanced nuclear technologies be, as some of their proponents claim, less prone to dangerous accidents?

In the years since those notorious meltdowns, the industry has made important safety advancements. But Dr. Edwin Lyman, a nuclear physicist and director of nuclear power safety at the Union of Concerned Scientists, thinks that many of the advanced nuclear technologies in the spotlight today are not likely to be much safer than nuclear power plants from earlier eras.

“We don’t have endless time. We have to address this problem now.“

— Dr. Allison Macfarlane

Part of the problem, according to Lyman, is that many of these technologies aren’t as “advanced” as industry would have you believe. “Most of the so-called advanced reactors are really repackaged designs from decades ago that were attempted but didn’t succeed,” he says. Today’s “innovative” technologies have designs similar to flawed projects from the 1950s and 60s: There was the Experimental Breeder Reactor 1 in Idaho, which in 1951 was the world’s first reactor to produce electricity — before an accidental meltdown damaged half its fuel in 1955. And there was Fermi 1 in Michigan, which suffered a partial meltdown of its reactor core in 1966.

Unlike the well-known meltdowns of history, these accidents didn’t result in any major release of radioactive material. But the technologies were discarded in favor of safer, more reliable reactors — which are what’s operational today.

Now industry is returning to those older, experimental designs, as the basis for some of the “advanced” technologies of today. To Lyman, that’s risky. He’s concerned that when it comes to some advanced designs, there are still questions without answers backed by rigorous data — such as the risk of fire posed by sodium coolants, and how well physical containment structures would work in the event of an accident. Security is another concern, with some designs increasing the risks associated with nuclear proliferation and nuclear terrorism.

MORE CLEAN ENERGY IS NEEDED TO POWER AMERICA’S FUTURE, and even many critics of advanced nuclear technology, like Macfarlane, aren’t advocating shutting down existing nuclear plants. “We definitely need that carbon-free electricity,” she says.

But nuclear isn’t the only zero-emission energy source on the table. Renewables such as wind and solar are quickly becoming cheaper. And while nuclear industry proponents have long scoffed at the reliability of these sources, this is far from the problem it’s made out to be, Dr. Amory Lovins, a Stanford University energy efficiency researcher, says. Wind and solar may be variable, but “variable does not mean unreliable,” he says — especially as modern wind and solar forecasting, significant improvements in battery technology, and other advancements are shoring up the reliability of renewable-heavy grids.

Unlike advanced nuclear projects that won’t come online commercially for years, renewables are adding valuable capacity to the grid right now. “There’s no way nuclear can address climate change in any timely fashion,” Macfarlane says. But renewables, by being cheaper and quicker to deploy, give us a chance.

In the long term, nuclear may well be part of the puzzle that helps the U.S. meet growing energy demands. It may even make sense for Wyoming to host new nuclear projects. But bringing nuclear energy to Wyoming isn’t something we should rush. Even if we speed ahead with advanced nuclear technologies, it’s not likely to add enough clean energy capacity fast enough to solve the climate crisis — and it is likely to expose Wyoming communities to unnecessary risks.

As Lyman, the nuclear physicist, says, speed isn’t the friend of safe nuclear energy. And asking important questions — about how industry and government plan to build projects responsibly, deal with waste, keep communities safe, and pay for it all — takes time.

It will take even more time, and surely many more public meetings stretching late into the night, to build a comprehensive state policy around nuclear energy.

But slowing down and making well-informed decisions could yield clarity. In a world of unknowns, that clarity may offer the strongest foundation for moving forward, on Wyoming’s terms.

Header image: An artist’s rendering of TerraPower’s planned Natrium nuclear power plant near Kemmerer, Wyoming. (Courtesy TerraPower)