Why your voice matters, even on losing battles

ONE DAY LAST SUMMER, I ran into an acquaintance in Laramie. It was June, and the battle around selling off public lands was at its peak. I encouraged my friend to call her senators and tell them to vote no.

She sighed.

“What good will it do?” she asked. “They’re not going to listen to me.”

I was stunned. This was a woman who had always struck me as politically engaged. If she wasn’t speaking up, who would?

My friend’s skepticism is not uncommon. Many Wyomingites are reluctant to contact their lawmakers, because they assume it won’t make a difference. But how true is that? Is there value in engaging politically, when it seems like a losing battle? How much difference can a small group of citizens make?

“People have a tremendous opportunity to influence legislation,” says Ryan Williamson, a political scientist at the University of Wyoming who specializes in American government and politics. “Legislators want to keep their job. They want to win reelection.” So they pay attention to what their constituents are saying.

Even if you are in the minority, you can make a difference, Williamson says. That’s because most people don’t speak up at all.

“Your average American, their idea of political engagement is maybe voting every four years,” Williamson says. “The high-performing American also votes in midterm elections. … But as far as direct contact with legislators, that is a very small subset.”

As a result, those who do reach out can have an outsized influence.

This is especially true in Wyoming, where each state lawmaker only represents a few thousand people. If they receive 50 calls about a certain issue, that’s a meaningful percentage of their constituency and could make or break legislation — especially on lesser-known issues, where a lawmaker’s mind isn’t entirely made up.

This scenario is not just theoretical; we’ve seen it play out in Wyoming multiple times.

One of the most recent examples was during last year’s legislative session. John Burrows, WOC’s Energy and Climate Policy Director, remembers the day vividly.

It was Jan. 29, 2025, and John had gone to Cheyenne to testify before the House Minerals, Business, and Economic Development Committee. The committee was discussing a bill that would allow Wyoming to become the dumping ground for the nation’s nuclear waste.

John felt an anxious weight in his stomach as he walked up the snowy steps to the Capitol. He knew the best chance to stop this bill would be now. If the bill made it over to the senate and passed into law, Wyoming would be liable to feel the consequences for thousands of years.

The committee room filled with people who came to testify. Others joined online. Everyone had questions.

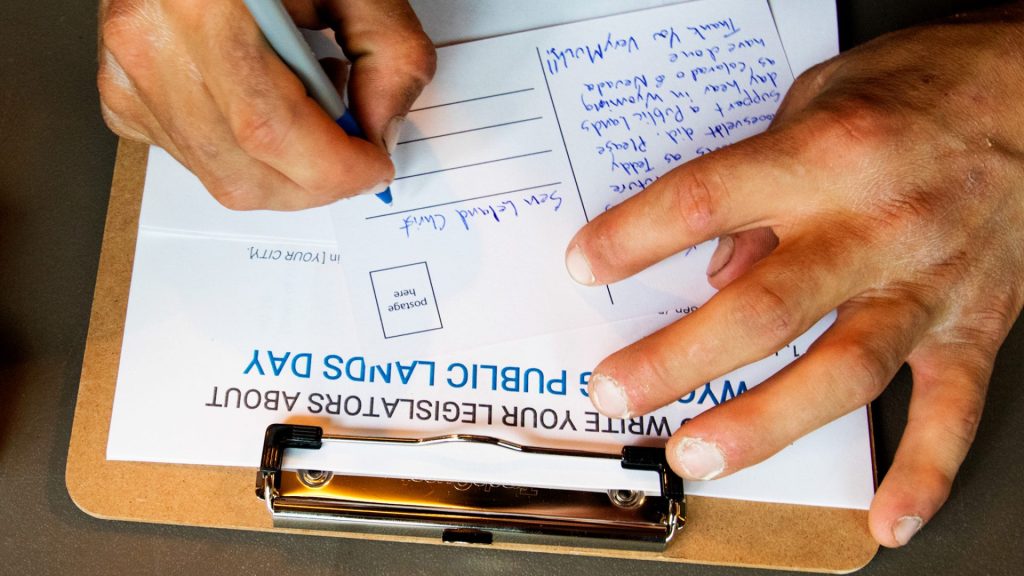

The meeting went on for an hour, then two. And then, one lawmaker made a comment that John knew would be pivotal. It was Rep. Mike Schmid of La Barge who spoke. “I’ve got hundreds of emails,” he said. “And not one is in support of … this idea.”

John’s pulse quickened. Hundreds of emails, he thought. And not one in support. Surely, lawmakers couldn’t ignore that level of public opposition.

Sure enough, the bill died that day in committee. Lawmakers couldn’t justify supporting a measure that their constituents so vehemently opposed.

A tiny win now could pave the way for a bigger victory down the road.

To John, this is a classic example of Wyoming’s small government at work.

“It doesn’t take as many citizens reaching out to have an impact as you might imagine,” he says. “A hundred or 150 people sending an email … can absolutely stop bad legislation from moving forward.”

This has happened on multiple issues over the years. In 2016, public outcry killed a bill that would have called for federal lands to be transferred to the state. In 2024, public pressure prompted the Wyoming legislature to agree to sell the Kelly Parcel to Grand Teton National Park. And year after year, legislation aimed at dismantling net metering — which allows rooftop solar customers to be compensated for the excess energy they feed back into the grid — fails because of steadfast opposition from citizens.

“Everybody’s coming out with a pitchfork saying, ‘No, don’t do this,’” John says. “And so that’s what keeps winning the argument around net metering.”

You won’t win everything. There are certain issues where lawmakers’ opinions are so entrenched that no amount of public input is going to make a difference. But even if you don’t win outright, there can be hidden benefits.

For one thing, speaking up publicly can raise awareness around an issue. It can help with fundraising efforts for the cause. It can even pave the way for recruiting new candidates for the next election cycle.

Secondly, politics is not a zero-sum game. Sometimes it’s not about passing a good bill, or killing a bad one, but rather about modifying legislation to make it more palatable. Baby steps count.

“Your average American kind of expects change to happen suddenly and substantially,” says Ryan Williamson, the political scientist we heard from earlier. “But especially if you’re in the minority, change is going to come, at best, incrementally.” A tiny win now could pave the way for a bigger victory down the road.

Finally, even if you don’t change a politician’s mind, you are still holding them accountable when you speak up.

“Even if one person reaches out … then that legislator can no longer say, ‘No one is opposed to this,’” Williamson says. You might plant a seed of doubt in their mind, and that seed could grow over the years as more people start championing the issue.

At the end of the day, Williamson says, you have to ask yourself if you are content with the status quo.

“If you care enough, you just have to trust that your contribution, at some point, in some way, will be meaningful,” he says. “Not to do anything would be a kind of implicit endorsement of the status quo.”

That is the mindset that Pinedale resident JJ Huntley lives by. JJ calls her lawmakers at least once a month, and sometimes more often. She focuses mostly on Wyoming’s congressional delegation — the people representing her in Washington — and she reaches out about a range of issues, from public land sales to federal layoffs to immigration.

This outreach has never — not once — made a tangible difference. Her lawmakers have never voted the way she wanted on these issues. But JJ is unwavering in her commitment to keep trying.

Part of it is personal: The process of articulating her position reaffirms her values. It reminds her of everything she loves about Wyoming. Partly, she wants to set an example for the next generation. And partly, it comes down to the belief that if she says nothing, she will be complicit in bad policymaking.

“If we aren’t talking, then we’re basically saying we don’t care,” JJ says. “There will not be a change. … I want my voice to matter, so I have to keep talking until it does.”

“If you care enough, you just have to trust that your contribution, at some point, in some way, will be meaningful.”

— Ryan Williamson

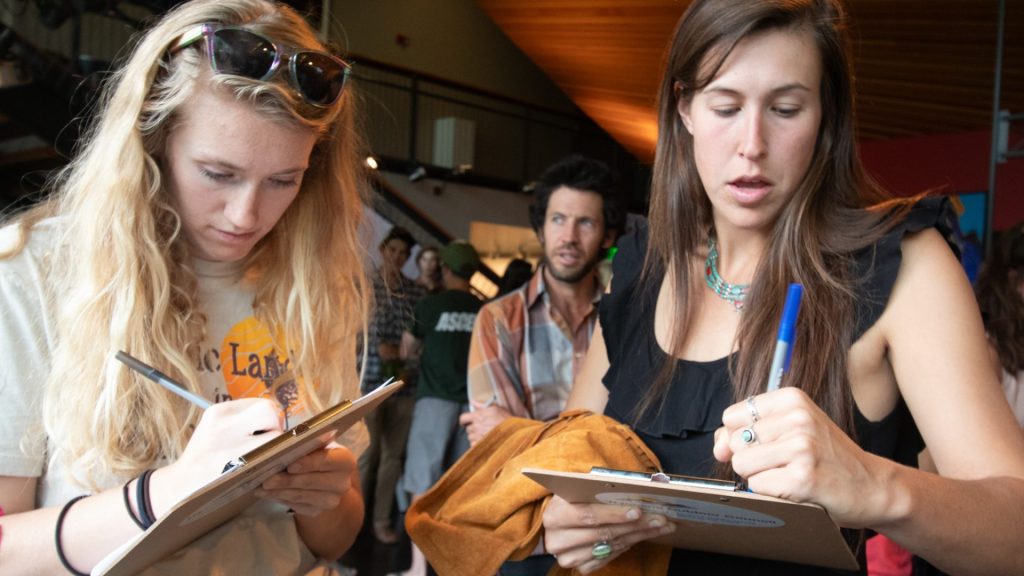

I recently attended a film screening in Laramie hosted by a Wyoming nonprofit. After the movie, the attendees sat around in a circle and talked about our hopes for the future. The executive director urged us to be vocal during the legislative session.

There was silence for a moment, and then one woman raised her hand.

“How much good will it actually do to contact my lawmakers about this?” she asked.

I nearly leapt out of my seat. “I can answer that!” I said eagerly.

I proceeded to tell her everything I had learned researching this story: how a small but vocal minority can influence legislation, especially in a state like Wyoming; how political engagement often has hidden benefits, even if you don’t win outright; how tiny victories add up.

We can’t know how — or if — our input will make a difference. But one thing is sure: If we don’t engage, we won’t be making a difference.

As Ryan Williamson put it, “Politics is hard. Change is slow. And it’s easy to get disenchanted. But the health of a democracy is dependent on engagement from the citizenry.”

If you’re on the fence about speaking up, he says, ask yourself this: “How would you feel knowing that you could have done something?”

Header image: Photo by Kaitlyn Baker on Unsplash